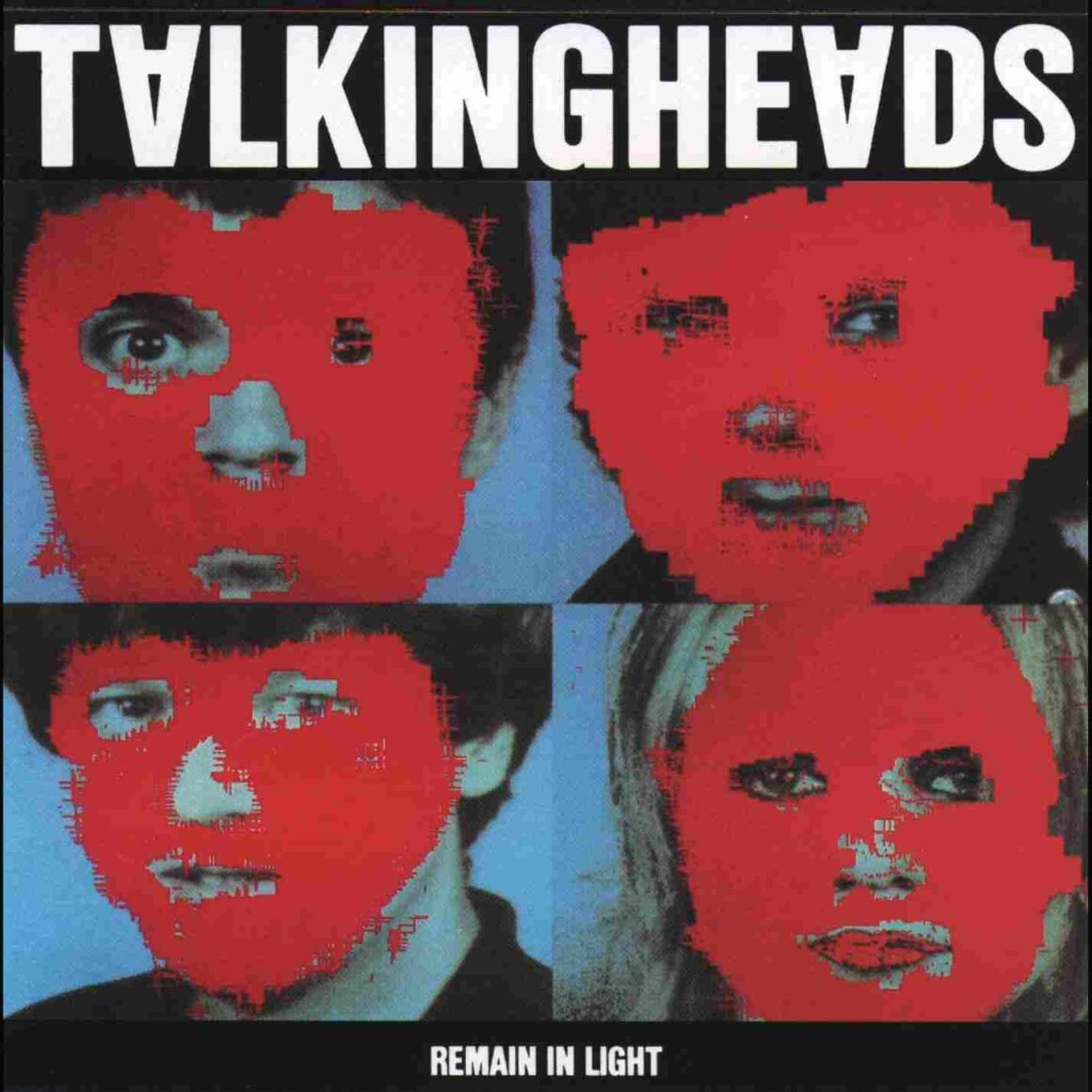

Breaking Genre Boundaries: Talking Heads’ Remain In Light

Revisiting an artistic blueprint of Popart, Indietronic and Afrobeat.

At the end of 1980, The Talking Heads were actually no longer a band. In spite of all the inner rifts that were going on between the members, they still released what might be the best album of their career. With Remain in Light, they were breaking genre boundaries, experimenting with African-influenced polyrhythm, rock steady and the rap of Fela Kuti.

If you listen to Remain In Light after the previous album without knowing the background story, it actually seems like a logical continuation. Talking Heads began their career as a fidgety, cerebral post-punk band, inspired by their New York contemporaries Television. On Fear Of Music, however, they began to experiment with tape loops and Afrobeat rhythms together with their producer Brian Eno. This could be clearly heard in the opener “I Zimbra”, a bizarre mash-up of highlife guitars and Dada poetry. It was precisely this polyrhythmic art funk that the band wanted to pursue on their next album. But then Byrne left the band.

Weymouth and Frantz had to almost lure Byrne into the studio. First, they started recording some loose jams together with keyboardist and guitarist Jerry Harrison. With “I Zimbra” as a model, they expanded the dense Afrobeat grooves even further and soon rhythms piled up wildly. They passed the result on to mastermind Brian Eno. The great musical innovator initially refused to produce the album but when he heard the first demos, he couldn’t help it.

Byrne and Eno had a guiding principle: to break all routines and destroy the musical comfort zone that the band had created from post-punk, funk and new wave on their previous albums. The most exciting thing about this album probably Byrne’s songwriting. He lets his surrealistic streak run free and yet doesn’t sound like a musician who wants to liberate himself intellectually. Byrne wanted to turn off the meticulous control in songwriting. In this way, despite all the encryption and remoteness, he manages to give his lyrics a very special meaning.

The opener “Born Under Punches (The Heat Goes On)” is driven by a choppy beat that seems to sprint and stumble at the same time. “Take a look at these hands,” demands Byrne with the urgency of an apocalyptic priest. Guest guitarist Adrian Belew ends the song with a solo that sounds like someone accidentally called a fax number. The individual elements often stuck together from different tape loops, might not seem to fit together. But they do, as a glance at one’s own hectic moving leg reveals.

And the madness doesn’t stop: “Crosseyed And Painless” is a banger, whose tightly interwoven basslines, drum patterns and guitar layers groove undeterred. In “Houses In Motion” Talking Heads almost sound like Parliament’s neurotic siblings – and at least as funky. The hit “Once In A Lifetime” oscillates every second between a hymn of hope and an existential crisis. The ballad “Listening Wind” offers surprisingly pure, unironic beauty, especially in Weymouth’s woefully descending two-part bass. This is not music that can be created by four fighters and hens. This is a band in its top artistic form.

The music that these five people created is still quite intangible and incomprehensible today. On Remain In Light, The Talking Heads let text and sound dance together, bringing poetry and pop to the dance floor as if it was already a matter of course in 1980. This record whose strange grooves resonate to the present day is magic that has become physically tangible sound. It is indeed an artistic blueprint of Popart, Indietronic and Afrobeat.

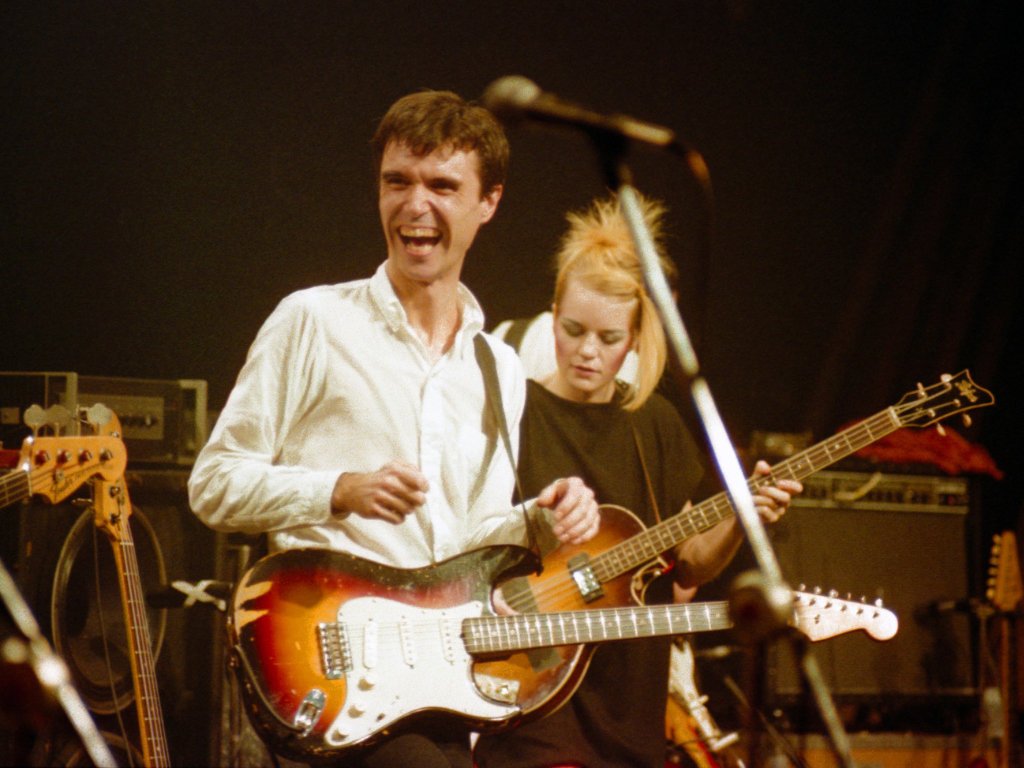

Talking Heads

Remain In Light

Featured Image by Craig Howell